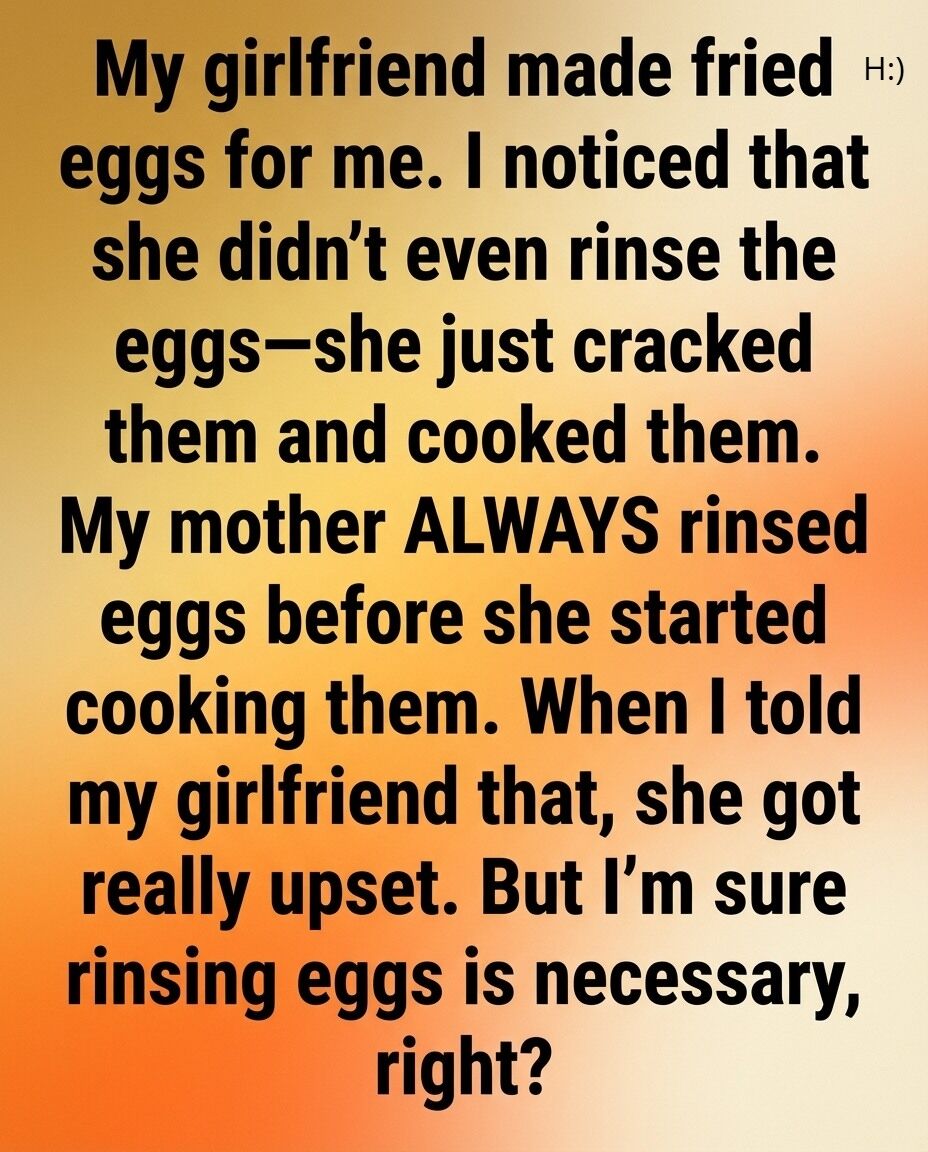

The vulnerability of an egg typically begins when human habits disrupt this original design through washing. In certain commercial systems, eggs are thoroughly cleaned soon after collection to remove dirt and potential surface contaminants. While this practice is intended to enhance hygiene, it has a significant side effect: it strips away the cuticle. Without the bloom, the shell’s pores are exposed. The eggshell, though sturdy, is naturally porous; thousands of microscopic openings allow gases to pass in and out. This porosity is essential for a developing chick, but it also means that once the protective coating is gone, external substances can move inward more easily. Water used during washing can facilitate this process, especially if it is cooler than the egg itself, potentially drawing bacteria through the pores by pressure differences. After washing, the egg becomes more dependent on artificial safeguards, particularly refrigeration, to slow bacterial growth and maintain quality. Constant cold storage compensates for the lost barrier by inhibiting microbial multiplication. However, this introduces a new vulnerability: temperature fluctuations. When refrigerated eggs are later exposed to warmer air, condensation can form on the shell’s surface, creating moisture that encourages bacterial growth. Thus, the removal of the bloom sets off a chain reaction that necessitates stricter environmental control. What began as a well-intentioned cleaning step can inadvertently make the egg more sensitive to handling conditions. This does not mean that washing eggs is inherently unsafe; rather, it underscores that once the natural shield is removed, the egg’s resilience decreases, and the burden of protection shifts entirely to human-managed systems.